Digital Holocaust Memory – 30 Years On

by Prof. Victoria Grace Richardson-Walden

We still often hear people talk about digital Holocaust memory in terms of ‘new media’, but the first Holocaust-related CD-ROMs were released in the mid-1990s. Our Lab Director reflects on the past 30 years of practice in this field.

There is still substantial hesitancy in both Holocaust Studies and Holocaust memory practice to critically engage with the broad range of digital media through and with which Holocaust memory is being shaped.

There is also a dominant normative mode of engagement that has emerged in which professional digital Holocaust memory practice tends to be grounded in simulation of pre-digital traditions of doing Holocaust memory. Given that Holocaust memory has developed with emerging technologies, from print documents, newsreels and wire recordings through different tape formats, including video through to the vast array of digital media today, it is important to conceptualise how each medium and media epoch brings their specificities to bear on this wider commemorative culture.

Perhaps it is not an issue that digital Holocaust-related projects reiterate norms of pre-digital ones. However, when they are more expensive and resource intensive on institutions, hardware, software, people and the environment to maintain, we need to ask ourselves whether such a ‘status quo’ is both productive and ethical?

Furthermore, whilst we should be wary of the simple idea that young people are competent users of new technologies, it is fair to observe that across the generations, the everyday life of populations today – whether they possess their own devices or not – are deeply shaped by digital media.

So then, we need to take a step back and critically define digital Holocaust memory, and adopt a more strategic engagement with such technologies which would mean replacing the current normative mode with a connective one. That is a mode which engages in computational logics on their own terms. I do not mean here to eradiate the human from this very human history, related memory cultures or indeed the humanities. Nevertheless, it is worth bracketing aside those domains with which we are more familiar to consider what specificities computational media bring to doing Holocaust memory for it is the very digitalness of digital Holocaust memory that we still seem often to ignore.

Better understanding the particularities of these media, and the applying this understanding to more critical approaches to using them will help ensure a more sustainable future for Holocaust memory in the so-called digital age. By sustainable, I mean, both in terms of maintaining the cultural relevance and prevalence of Holocaust memory as well as best use of resources, on ecological and economic terms.

Why Bother?

The Holocaust heritage and memory landscape is not particularly digitally ready, not just in terms of having full-time, permanent staff in institutions who can code, programme, use CMS backends, and create digital images but also at the level of understanding the potentialities of particular technologies, and the socio-political consequences of digital development.

However, there are many bad actors who are sophisticated digital agents. Who can set up bot farms, matrix networks, and targeted misinformation, doxxing and trolling campaigns. It is not simply particular individuals, organisations or governments that one needs to be wary of. The vey logics of Web 2.0 encourage problematic content to be made more visible as controversy garners more hits and thus produces more data. The techno-libertarianism that has driven Silicon Valley is revolutionary in intent, but not in a way that promotes the nuance needed for Holocaust memory and heritage. In fact, much the opposite, it embraces and encourages diverse voices to the extent that expertise is flattened, ‘truth’ matters less than everyone’s voice being heard, and governance is resisted.

We could say, well let us stay away from digital technologies – are they not inherently bad? But that would be a mistake on at least two accounts:

- Whilst technologies are never political neutral, their lack of neutrality is due to the fact they are always already socio-technical. That is, from the moment they are developed, human individuals situated in both institutional and cultural contexts define what technologies do. We cannot simply disregard ‘social media’, ‘virtual realities’, ‘the internet’, ‘computer games’ or any other digital media, platform or space as useless for Holocaust memory, just as we cannot disregard all literature ever written just because someone writes a novel about Auschwitz that we consider to be abhorrent, or indeed disregard radio because it was a successful propaganda mechanism during the war.

- Furthermore, Holocaust memory circulates widely in digital spaces whether heritage, memory and education organisations are present or not. We can either let those with no or limited expertise write Holocaust memory through the digital media that prevails in everyday life, or we can take on the responsibility of working with the logics of these socio-technical ecologies to play a role in shaping the future of our domain as we want it to be.

What has digital Holocaust memory looked like over the past three decades then? Let’s take a look…

Digital Holocaust Memory over the Past 30 Years

As this blog’s title suggests, we are soon approaching 30 years of digital Holocaust memory practice. With the World Wide Web entering the public domain in 1993, professional Holocaust memory institutions were rather slow to embrace the internet and emerging electronic technologies. As our esteemed colleague Prof. Eva Pfanzelter (University of Innsbruck) noted recently at our Connective Holocaust Commemoration Expo, in the early years, Holocaust memory online was really the domain of private individuals. Nevertheless, the 1990s did see a range of emerging initiatives from the first museum websites (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 1996) through educational CD-ROMs, concentration camp panoramas, and online ‘exhibitions’.

Screenshots taken from the Wayback Machine of impressions of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum on April 3rd 1997 (https://web.archive.org/web/19970403043412/http://www.ushmm.org/index.html)

Tim Berner-Lee’s ‘Hypertext Transfer Protocol’ (HTTP) and ‘Universal Resource Identifier’ (URI) system, which became known as ‘URL’, allowed HTML documents to be communicated over the internet. Thus, what we see in the early years is text and image-based content. HTTP was designed to allow information to be transferred between computer systems, and with the World Wide Web, this enabled global circulation. This was the era of Web 1.0.

In these early years, Holocaust memory on the World Wide Web was dominated by amateur players and associations as Pfanzelter astutely observes. It is noteworthy that urls now owned by major institutions, such as the Anne Frank House and Yad Vashem, lead in the Wayback Machine archive to non-official sites (as illustrated in the images below). Professional Holocaust organisations were late to recognise the internet as a space for memory practice, and as more broadly typical of 1990s web culture, memory was being performed from below, and key figures and institutions were co-opted within these community spaces.

Wayback machine capture on November 9th 2000 of the url which now belongs to the Anne Frank House. It does however provide a link to the official museum’s page.

The link to the official museum page takes users of the Wayback Machine here – to its imprint from December 10th 1997, where the site simply provides key information about what the Anne Frank House is, where it is located, and when to visit.

Nevertheless, the Anne Frank House, in particular, was one of the earliest explorers of emerging media thanks particularly to Gerrit Netten, now Head of Digital there (whose interview will soon be available in our Digital Memory Database). Gerrit led the development of the CD-ROM Anne Frank House: A House with a Story, published in 1999 which explored the possibilities of hyperlinked, non-linear narratives for the first time in a Holocaust memory context.

It is at this moment, with the gradual shift from Web 1.0 to Web 2.0 (c. 1999-2004), that we see the emergence of what I call a playful mode of digital engagement. Some, early adopters in Holocaust commemoration contexts were curious and explorative, taking time to consider what the specificities or affordances of a particular technology, software of platform could offer, and shaping Holocaust memory through these logics. Alongside, the Anne Frank CD-ROM, other examples include:

- The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Witnessing History: Kristallnacht, the 1939 Pogroms in the virtual world-building online platform Second Life (2008) [Discussed in more detail by the team behind it in our first Dialogue here]

- The Oshpitzin app created by the Auschwitz Jewish Center, Poland – a precursor to AR mobile tours [Discussed in our Spotlight blog here] blended a drawn map influenced by a illustration of the town by a returning survivor with images and text, encouraging users to take exhibition out of the museum into the town

- Brama Grodska Cultural Centre, Poland established a Facebook page for the child victim Henio Żytomirski (2009). Whilst previously it had been traditional for Polish school children to write a letter to Henio, now they could also send him invites to play games and wish him Happy Birthday

- 2014 saw the launch of Spaces of Memory, the first of the Future Memory Foundation projects which used 3D reconstruction techniques to create VR and AR experiences of the Bergen-Belsen Memorial to encourage experiential learning in contradistinction to the typical guided educational tours

- The Wiener Library, UK held live Twitter debates (2015), running hybrid events with audiences both in the London library and online posing questions about Holocaust memory practice. They would then use the now defunct app Storify to create a thread of the conversation collated computationally through a shared hashtag

- In 2017, Charles Games, a spinout of Charles University, released Attentat 1942 which engaged in thorough user testing with school classes to explore how games could be used to develop learning about the Holocaust-era in what is now Czechia. This is not simply ‘playful’ because it is a game, but playful in the explorative sense because it was a pastiche of different interactive and aesthetic styles, from using photorealist filming for interview scenes, in which players must choose responses to move the story forward, to collage interactive scenes riffing off avant-garde Czech animation styles, through to full comic book graphics of playable historical scenarios, and an encyclopaedia which users populate by discovering new words through the game

- Yad Vashem’s iRemember Wall, which originally linked user’s Facebook profile names to a Holocaust victim from their Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names using APIs at the backend was launched in 2021.

Yet c. 2020, there was clearly a standardisation of practice emerging – although not informed by any discussed, agreed or published standards. This defines what I refer to as the ‘normative mode’. In this mode, we see the particular affordances of different media, platforms, and software being deprioritised for the sake of using them to create experiences that follow formats belonging to the broadcast era. Examples include:

- Instagram live tours which recorded actual on-site tours, albeit in shorter form (see our blog covering one example of this)

- Social media posts acting like exhibition boards with historical information, quotes, citations, and photographs

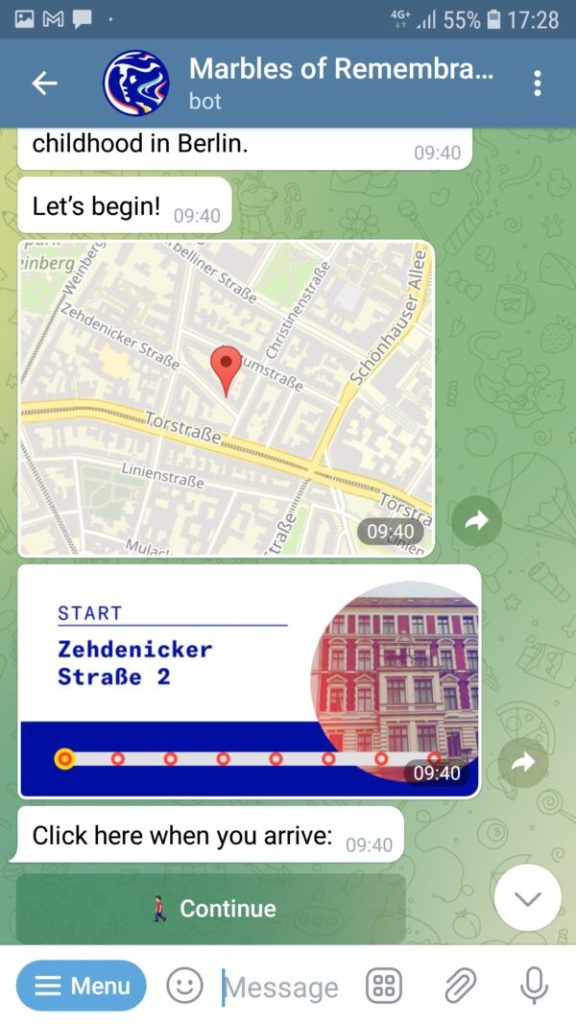

- Messaging apps, like Telegram used for guided tours, rather than as a community messaging platform (such as Marbles of Remembrance, which has now been added to a broader Berlin tours app)

- Survivor testimonies and survivor return narratives delivered in 360/ VR, for example The Last Goodbye (USC Shoah Foundation, 2017), Letters to Drancy (Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Centre, 2023), and Walk with Me (Melbourne Holocaust Museum, 2023 [discussed in our Spotlight piece here])

- Furthermore, a norm appeared in games to settle on the point and click interactive story that was one part of Attentat 1942 dismissing the other potentialities that game explored (see for example the National Holocaust Museum’s Journey app (2020), and The Light in the Darkness (2024)

- However, another trend appeared in computer games too – that of the Remembrance Game genre, which was particularly popular in Germany. Cautious about making the Holocaust playable, yet wanting to engage with the format, memory professionals and academics settled on framing games through a post-Holocaust lens (see for example The Children of Bullenhuser Damm, and #LastSeen).

- Most recently, we’ve seen attempts to use Gen-AI models to amalgamate historical photographs and survivor testimony to give the appearance of the child-like or younger survivor (as they were in the historical time of the Holocaust) speaking their testimonials given many decades after the war. See for example projects by Generative AI for Good and Never Again Young Again. Such an approach is a very clear example of the simulative mode, focusing on trying to replicate broadcast logics rather than thinking about what can this technology offer anew?

Screenshot of Marbles of Remembrance when it was on the Telegram App. Replicated here under fair use policy.

What Then Distinguishes the Connective Mode?

As I long ago outlined in my methodological blog, from Intermediality to Entanglement, there are multiple levels of connectivity that define the digital – in fact, it might be best to describe digital ecologies as hyperconnective. We are seeing hints of an acknowledgement of this connectiveness in different ways in some digital Holocaust memory projects:

- Dimensions in Testimony (DiT) (USC Shoah Foundation) as a system constantly updated based on human-computational symbiosis in learning; as asset-based so offering the ability to embed DiTs into different digital projects (for an example see the VR experience Inside Kristallnacht)

- The Volumetric Contemporary Testimony of Holocaust Survivors digital archive created by Filmuniversität Babelsberg Konrad Wolf, which sees these recordings again as assets to be migrated into different outputs, for example Die wenige Zeit

- Some archiving and collecting projects have decentralised their work, connecting more explicitly with their audiences as collaborators, for example #EveryNameCounts (Arolsen Archives); History Unfolded (the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum); JoodsMonument (Jewish Cultural Quarter, Amsterdam); and the Library of Lost Books (Leo Baeck Institute and Queen Mary, University of London)

- Others are connecting through prioritising linked and open data, such as Verbrannte Orte and De Tweede Wereldoorlog dichtbij (albeit the latter is more focused on World War II rather than Holocaust collections)

- Then, there are approaches to being connective at the infrastructure level. First this happened via the establishment of portals such as the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure and more broadly, in the wider heritage sector, Europeana, then more recently there has been a turn towards data spaces (Europeana has followed this trend and a new initiative the European Memory Data Space blueprint is focusing specifically on Holocaust memory)

- More collaborations are occurring between professional creative and tech players, from platforms (Meta were involved in both Inside Kristallnacht and the World Jewish Congress and UNESCO’s #WeRemember campaign, as were other platforms), influencers (see the example of Montana Tucker working with the Claims Conference on Holocaust Remembrance: Never Forget, Never Again released on TikTok, YouTube and elsewhere), to smaller creative and tech companies such as &Why (#LastSeen) and Paintbucket Games ( The Children of Bullenhuser Damm) [Read our article on hyperconnective and TikTok here]

- Both corporate and academic groups are also developing Content Management Systems and/or methodologies to support easier access and more sustainable, repeatable approaches to creating digital experiences in the field too (for example ZaubAR, Future Memory Foundation, and the Neueste Geschichte und Historische Migrationsforschung der Univeristät Osnabrück).

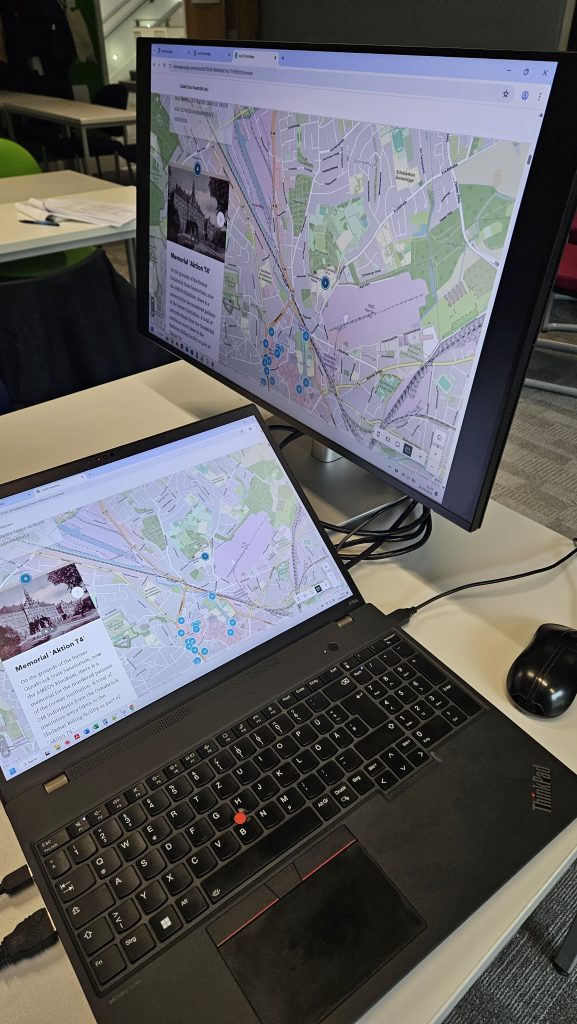

The Osnabrück University team demonstrating their lo-tech methodology to supporting participatory approaches to digital history work.

Digital Holocaust memory is…

Practice which makes use of computational and human logics of communication for the sake of public memorialisation of the Holocaust.

It brings Holocaust memory into today’s digital ecology, which functions across three different levels:

Micro: it is informed at its base by data and information circulation thus reconfigures the principles of Holocaust memory

Meso: through the principles of computational media (as outlined by Lev Manovich [1999]) it connects technological systems to human users

Macro: it also functions at a network level that connects technological systems, users, and cultures across the world in a continuous flow.

It is worth thinking more deeply about each of these levels:

Digital Holocaust Memory at the Micro Level

To start at the micro level reminds us that digital Holocaust memory is situated within the so-called ‘Information Age’. This ‘Age’ it is not only about sharing information, but information (or ‘data’) is what maintains the profitable industry that keeps us compelled by the idea that we need to keep making digital stuff and thus we are coerced to keep sharing information. Whilst the Information Age is considered to have replaced the ‘Industrial Age’, it is no less shaped by capitalism logics of extraction that its predecessor.

Not only does it perpetuate at exponential rates, the extraction of rare materials from our planet, battles over which offer spur global conflict, civil unrest, poverty, disease, and irreparable damage to ecosystems, but its distinction from the Industrial Age is its reliance on the extraction of data from individuals – with / without consent. It is worth being really explicit here: this fundamentally conflicts with the ethical grounding of Holocaust memory which focuses on human rights and dignity not encouraging conflict and dividing society.

Beyond simple extraction, the profit and innovation-for-innovation’s sake of these sectors develops further through the aggregation, packaging and rearranging of this data. Esteemed media and communication scholars Ulises A. Mejias and Nick Couldry argue that we are seeing a new form of ‘data colonialism’ which not only shapes the social order but appropriates human life. Nevertheless, in their book Data Grab: The New Colonialism of Big Tech and How To Fight Back they argue that resistance is necessary and possible despite being challenging.

This bleak description of information and data is a ‘pulling back the curtains’ on the commercial, so-called ‘Californian Ideology’ that drives Silicon Valley and ‘tech startup’ approaches. This is but one way in which we can conceptualise the use of information and data … it is not inherent within digital technologies themselves, but in the dominant narrative of how we are told we should use them.

There may be hope …

Holocaust memory culture is a prime space in which this approach could be challenged. Holocaust museums and archives are not seeking large swathes of personal data of contemporary users (although many of their digital projects collect these!); however, they hold vast collections of incredibly sensitive narrative about the history of individuals – both those living and deceased.

Holocaust memory organisations have decades of experience in considering how best to disseminate such content, from debates about the curation of atrocity photographs and human remains through to testimony recording methodologies and discussions about the ethics of rearranging and editing survivor testimony into digital formats.

In essence, professional Holocaust memory-makers want to disseminate truths – as much as they are known – in nuanced ways to publics to help them know about this enormous ‘event’ and its global impact on the world, and to reflect on its significance (whether this be for universal, contemporary, or historical).

Yet, currently, a significant amount of digital Holocaust memory practice (in the professional realm at least) focuses on simulating historical modes of both broadcast age media logics (e.g., film) and of Holocaust archive and museum logics (e.g., site visits, testimony). It mostly functions thus in what I have called the Simulative Mode.

Cynically, this means spending a lot of money (c. a relatively basic AR mobile app can cost E450,000) for projects that often don’t last very long (due to a lack of investment in digital infrastructure and hardware/ software maintenance) and don’t do anything particular new for Holocaust memory, yet might insidiously contribute to the extraction-driven ideology of the commercial tech sector.

This is not a particularly productive or sustainable model. Furthermore, it is not an ethical one.

To better understand how we might move away from the simulative mode to a more sustainable one, that leverages the specific principles of digital technologies for good perhaps we need to ask whether non-digital methods might also be better for our aims.

If we do want to ‘go digital’, then we need to go back to the core principles of computational media to fundamentally understand what it means to ‘go digital’.

Digital Holocaust Memory at the Meso Level

Lev Manovich (1999) introduced five principles of computational media and they still hold true today. Despite the seemingly fast-paced, ever-changing digital landscape we seem to face, at the principle level things have been entirely stable over the past three decades.

Manovich’s principles and their potential significance for Holocaust memory are outlined below:

Numerical presentation transforms humanities source and narratives into ‘data points’ and ‘file paths’ to be found through code, it calls for arrangement in databases where content is called upon to be made ‘discoverable’ and the use of probability, algebraic and statistical models to inform algorithms. It is probably the area that causes us all to feel the most uncomfortable in regard to Holocaust memory because it echoes the use of ‘punch cards’ to process people as ‘data points’ during the Holocaust itself. Nevertheless, this was a particular use of proto-computation not inherent to the technology itself. Numerical presentation supports working at scale and at speed, and offers potentially new ways to arrange information which can open up possibilities for humans to analyse different connections and lesser-known narratives.

Earlier, I mentioned there is the potential here for a reconfiguration of Holocaust memory, which I have elsewhere argued calls for a departure from conceptualising Holocaust memory through the lens of ‘representation’ (that is cultural-situated linguistic, aural and visual codes) to the lens of ‘mathesis’. This feels uncomfortable in the Holocaust context, and yet, if we want to engage with computational technologies for the sake of Holocaust memory, we have to recognise that they arrange historical and contemporary assets related to this past through mathesis rather than representational logics. We should either work with this or resist it, and the only resistance is not to use these technologies.

Modularity – in these databases, each ‘bit’ of information can be called up separately, it can be reused and removed, detached from its original context, but (and this is important for Holocaust memory) without the original ‘whole’ being damaged.

Variability – complementing modularity, this refers to the ability to remix and recontextualise data enabling us to compare large swathe of experiences of, for example, roll call on a particular day in Mauthausen in several testimonies, reports and other sources.

Automation – from menial to complex tasks, computer systems have long been designed to do some tasks for us. This might be processing data through to preparing templates for presentation. We need to separate the Californian myth of ‘Gen-AI’ and Automated General Intelligence and ‘Agentic Intelligence’ as the inevitable ‘automation’ future from other possibilities of automation.

Transcoding – is the act of translating the numerical presentation of programming language through human-readable code into something that has cultural value and meaning in our world, and vice versa. This is perhaps the most challenging principle that is often overlooked by commercial tech companies. When the rationale for doing a project is ‘innovation’ or ‘technology-driven’, then the cultural significance is deprioritised.

Transcoding happens at the permeable barrier we called the ‘interface’ between user and computer system, which we must understand as the ‘contact zone’ between the human and computational. It is one of a few visual and material signifiers that highlights that digital Holocaust memory is always a symbiosis between us and machines.

How, then, can we develop UX design and user journeys with tech stacks that allow computational and human logics to entangle in ways meaningful for Holocaust memory, and that do something different?

Why do something different? Does this not just perpetuate the ‘innovation’ myth? I would flip this question and say why spend more to do something digitally with the higher risk of technological obsolescence when you could spend less to do it non-digitally in a more stable format?

If we’re going to do digital Holocaust memory in sustainable ways, we need to use resources appropriately – we should not be complicit in wasting money or damaging the environment for a quick ‘jolly into AI’ when the project could have been done without that tech. Furthermore, we need to remember that our intentions matters – digital outputs are not informed solely by technology, but by the humans involved in creating them.

As Critical AI Studies scholar Simon Lindgren (2024) argues in terms of ‘AI’, we talk too much about ensuring there is a ‘human-in-the-loop’ when it would be better to conceptualise projects in terms of where the ‘AI’, or I would argue more broadly the ‘technology’ comes ‘in-the-loop’.

Todd Presner (2024) calls for an ‘ethics of the algorithm’, which brings traditional humanities methods of managing sensitive materials related to this past with computational ones in complementary ways that acknowledge the possibilities and limitations of both, whilst reaping the benefit of blending quantitative and large-scale data analysis with qualitative close reading. Despite the much discussed ‘close/distant’ reading dichotomy of humans V machines, Alex Lerner and Andrew Gelman (2023) recently demonstrated how engaging in computational techniques can actually enable us to read testimonies closer than we otherwise would have.

In practice, the more data we both digitise and produce a new related to the Holocaust (from the discovery and restoration of historical documents through to newly recorded testimony), the harder it becomes for any single human or group performing a particular methodology to examine this at scale through traditional methods. Engagement with computers for the sake of Holocaust memory then further adds to the abundance of data, necessitating more computational support to manage it. Nevertheless, to enable a symbiotic relationship between computational and human logics, through the lens of an ‘ethics of the algorithm’ (or perhaps better, an ethics with the algorithm) relies on mass digitisation on a global scale with agreed standards for metadata. Whilst ambitious projects like the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure (EHRI) and the European Memory Data Space go some way to addressing this issue, their reach is not as widespread as is necessary to have a truly, globally connected digital Holocaust memoryscape.

Data Spaces taking advantage of Web 3.0 technologies like Berner-Lee’s newly announced SOLID PODs promising solutions to data sovereignty and decentralisation, yet we should hold onto our scepticism somewhat – they are still technological solutions to problems introduced by technology!

Nevertheless, this brings us to the last point of my definition – the Macro-level.

Digital Holocaust Memory at the Macro Level

Now, we need to turn towards our networked society. ‘Bad actors’ – whether they be Holocaust denier groups, Governments or State militaries – have developed increasingly sophisticated methods for leveraging the specificities of networked communication. These range from ‘bot farms’ in the Republic of North Macedonia to matrix campaigns, cyberwarfare to connecting facial recognition software to social media pages for the sake of propaganda that is equitable to war crimes.

Despite the fact ‘the Holocaust’ was a globally networked event, and despite the fact a number of attempts have been made at international connectivity as exemplified by the establishment of the IHRA – there is no globally strategic and connective approach to digital Holocaust memory practice.

The majority of the projects on our map of global digital Holocaust memory are ‘siloed’, that is to say ‘one off’ projects more akin to a temporary exhibition, whether online, out on-location, or situated in a museum/ memorial site. Sometimes they ‘tour’ to other sites, following the temporary exhibition logic further. A few projects, take for example Houses of Darkness and the work of the ‘Future Memory Foundation’ connect a number, but still limited range, of sites.

Notably, they are primarily individual digital outputs – narrative expositions presented in a digital format rather than collections of digitised assets available easily for reuse (e.g., they are not prepared in a way that prioritises thinking about modularity and variability).

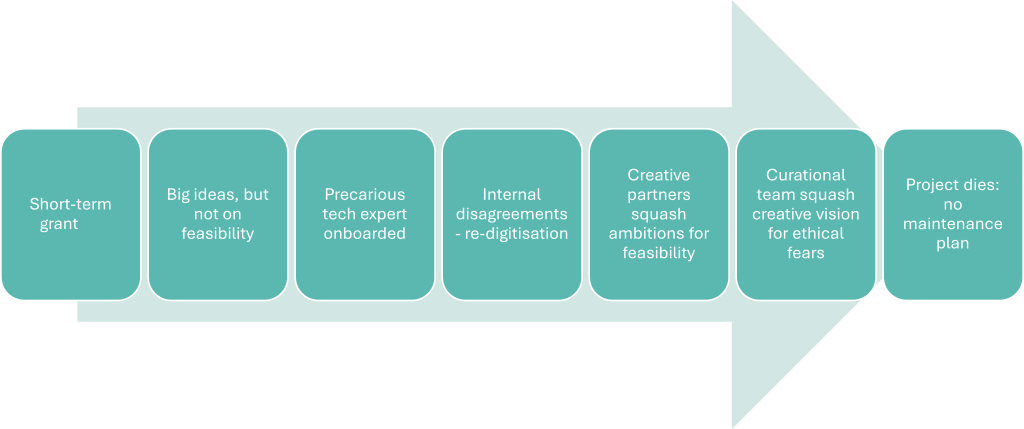

Many of our research interviews with people who have worked on digital projects in Holocaust institutions have presented a similar narrative to us as illustrated in the image below:

Very few projects are conceptualised through a computational perspective first, which would enable a more networked and sustainable approach to digital Holocaust memory by allowing assets to move between different outputs across multiple sites.

Adopting this approach would slowdown the speed at which we are seeing digital Holocaust memory outputs produced, but in the long-term it would enable more sustainable practice and actually maximise reach and impact.

To get there however, there are numerous cultural barriers that need to be resolved:

- Museums and memorials need permanent staff dedicated to digitisation and digitalisation

- They need long-term digital strategies (even if the strategy is anti-digital!)

- Organisations need to work together on coordinated digital efforts, sharing digital assets and engaging in data spaces

- They need to develop communication matrixes, and use the strategies and techniques of bad actors for good

- Funders and governments need to support digital Holocaust memory seriously, with less ‘short-term project-driven’ initiatives and more tranche-based support for national and international interventions

- The IHRA and other international groups need permanent spaces for developing these support needs. And the outputs of these permanent spaces or groups need to trickle down to the places it matters most – on the ground, in the comms, research, and education teams of museums, archives, memorial sites and libraries.

Many of these recommendations were highlighted in our recent working paper for the United Nations and Holocaust Outreach Programme.

Towards a More Sustainable Approach to Digital Holocaust Memory

If we are going to use digital media for the sake of Holocaust memory on their own terms, we need to work more connectively. We can start this by thinking more computationally which means:

- Prioritising large-scale strategic digitisation and tagging assets rather than ad-hoc digitisation being driven by output needs – we need to start with the data not narratives

- Decentralising collecting and dissemination efforts

- Engaging with linked and open data approaches

- Connecting sites together at and beyond the interface

- Working collaboratively and coherently (at scale) offline

- Reusing and sharing existing infrastructure and collaborating to inform any necessary new ones.

Digital Holocaust memory is a socio-technical phenomenon deeply embedded in today’s digital ecology.

A sustainable approach to the future of Holocaust memory means all of us working together, but also recognising the specificities that the technologies, models, hardware, systems, and software of ‘the digital’ bring, and better working with them too.

This blog is an abridged version of the keynote talk delivered by our Lab Director, Prof. Victoria Grace Richardson-Walden at the annual conference of the British and Irish Association of Holocaust Studies on 3 July 2025.

Join our survey here.

To learn about and test our database, please click here.