Spotlight: Gathering the Voices

by Prof. Victoria Grace Richardson-Walden

Our Spotlight series takes a deep dive into the digital offerings of worldwide organisations dedicated to Holocaust memory. This week, Prof. Victoria Grace Richardson-Walden looks at how the community association Gathering the Voices has used digital media to present testimonies of survivors with connections to Scotland, and to enable students to learn about their experiences.

As their first digital comic details, Gathering the Voices is a community association with six trustees, based in the Glasgow area. The trustees are three married couples, and the husband of each had at least one parent who experienced the Holocaust. It is a personal project, and the trustees have been able to collect c. 50 interviews because they had developed a substantial level of trust with many interviewees before the project started.

It was initially established with a small grant from Sense Over Sectarianism and a gift of several audio recorders that were going to be thrown out by Glasgow Caledonian University (where one of the trustees worked). Since then, the trustees have done immense work to apply for further funding, receiving support from the Heritage Fund which needed to be matched. Nevertheless, it is mostly sustained by a serious amount of good will! Beyond the trustees, who bring a wealth of expertise in curricula and pedagogy, they have developed relationships with one of Scotland’s top recording studio producers: Duncan Cameron, key colleagues at Glasgow Caledonian University, Magic Torch Comics, Bruclay Media, and Poppy Scotland. Many of whom I interviewed recently to include their experiences in our database-archive.

Gathering the Voices does not simply have digital projects, it is essentially digital. The Association has no permanent, physical education or exhibition space. Since it began in 2009, its core aim has been to collect interviews with ‘Holocaust survivors who have made their home in Scotland’ and to ‘make these testimonies available on the World Wide Web’, in order to ‘educate current and future generations about the resilience of these survivors’ (Shapiro, McDonald, and Johnston 2014).

Screenshot www.gatheringthevoices.com, with permission from Gathering the Voices.

The Association has always been dedicated to ‘openness’, wanting to treat the testimonies as Open Educational Resources (OER). However, over the years, the trustees have gone back and forth regarding their position on openness, recognising a tension between fears of misrepresentation and misuse of the interviews and the desire to make them as accessible as possible (Shapiro, McDonald and Johnston, 2014).

Whilst professionalised testimony archives have the capacity to develop interview, transcribing and indexing methodologies and standards, to-date there is currently no indexing of the Gathering the Voices testimonies, and the published transcripts were typed by hand. Nevertheless, they present a range of interviews on their website – not just those they have recorded, but videos of talks in schools, and radio interviews, and bring these together with their recording and ephemera from the survivors’ lives (e.g., photographs and drawings). Thus, a constellation of the individual people is provided. Central to the project was the idea of presenting the interviewees as more than just survivors, but also as people who have contributed to Scottish society in a myriad of ways. Nevertheless, survivors tended to talk at length about the years of Nazi occupation. Indeed, this was even true when we conducted interviews about their reflections on digital representations of their stories.

True to the Association’s name, what struck me most about all of its digital work is the significance of the survivor voice – whilst so often the digital and human are considered through a competitive frame (e.g., discrete v continuous; technical v organic; distant v close reading), Gathering the Voice’s digital work always emphasises the orality of the survivor, whether this be via quoting them verbatim when designing comic books illustrating their narratives, or embedding the actual audio recordings into computer games. As Shapiro, McDonald and Johnston note (2014),

‘the voice is a powerful tool’.

Throughout my recent interviews with several of the actors involved in their work, sustainability was a key issue but materialised in different ways. On one hand, there was the issue of preservation and the longevity of maintaining the testimony recordings in themselves. Interviewees noted that there are two key points in the technical pipeline that help ensure the long-term preservation of the audio files. Firstly, the quality of the master copies. Thanks to the types of recorders donated (Zoom H4s) and the post-production work of Duncan at Riverside Studios, the trustees recorded in .wav files, which were ‘topped and tailed’, had background noise minimised where possible, and balance so the difference in recording location between testimonies was inaudible. Quality not only retains the fidelity of the voice and personal story but is essential to ensuring the files last a long time.

Secondly, thanks to the work of Aidan Johnston and Jeremy Bailey at Glasgow Caledonian University, the trustees have digital infrastructure experts on hand. Their knowledge continues to inform ways to ensure the portability and discoverability of the site’s digital assets, from maintaining meta data standards (Dublin Core), offering a range of derivative versions of the .wav masters, and thinking about ways to chunk and connect content using code and AI in the future.

While these examples focus on technical solutions to sustainability, there is also always a human dimension to ensuring memory work continues and Gathering the Voices recognises this through its educational activities. Besides, resources to use in the classroom, they have also engaged in three co-production processes embedded into students’ learning at Glasgow Caledonian University and Saint Andrew’s & Saint Bride’s High School. As Paul Bristow from Magic Torch Comics shared, there is always a tension between the solemnity of memorialisation and the need to educate, but ‘you have to go where the people you want to engage with are’.

In 2014, Gathering the Voices partnered with colleagues in what is now called, the School of Science & Engineering for a game jam in which students had 48 hours to develop a game based on one of the Association’s testimonies. Whilst several excellent ideas emerged, Gathering the Voices was able to financially support one group to spend the summer making the first game Marion’s Journey (v1.0), but it was created in Adobe Flash, which was discontinued. A new version was later made by graduates from Glasgow Caledonian University (Chimera Tales), supported by their former Senior Lecturer Hamid Homatash. This is the version that now sits on the Gathering the Voices’ website.

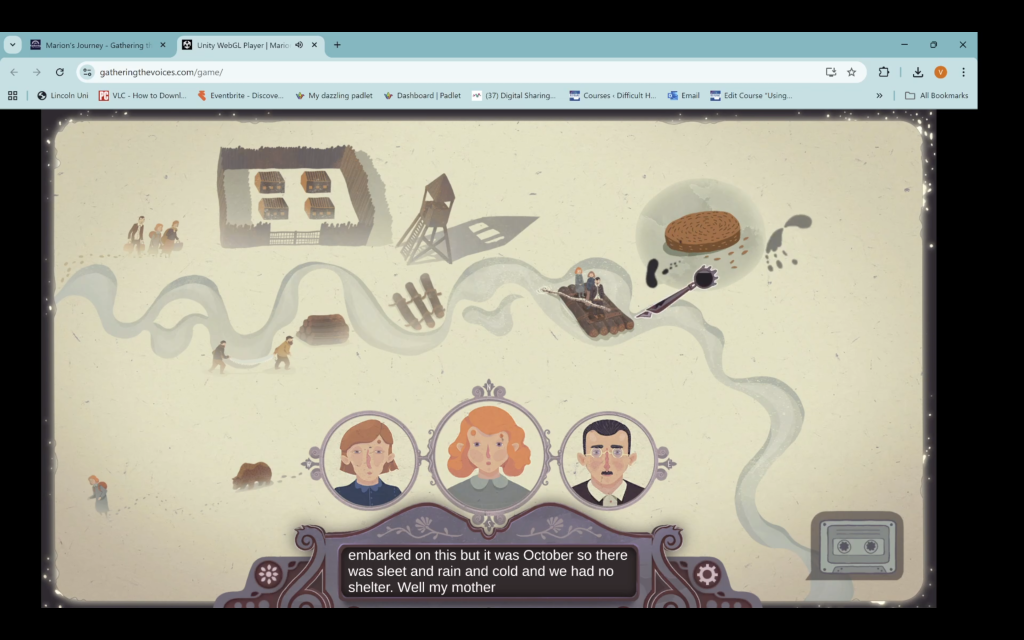

Marion’s Journey v2.0 presents players with a blank canvas that they need to scrawl over with a pen that produces ‘magic ink’, revealing glimpse of pictures – Marion’s memories – as it is moved. Whenever the next memory in her story is revealed, a segment of audio plays. The illustration in the game is reminiscent of the graphics of a large, hand-drawn map one of Marion’s friend’s children drew, representing her incredible trip East from occupied Poland to Siberia, then to Kazakhstan (which Marion kindly took the time to show me during our interview). Whilst Marion was surprised that students (and then later Chimera Tales) had decided to transform her testimony into a game, she did not seem concerned about this approach.

Screenshot from Marion’s Journey, with permission from Gathering the Voices.

Hamid Homatash also introduced Gathering the Voices as a client in one of his project-based modules available to Year 3 students across the faculty. This time, over two trimesters, students developed a game based on the testimony of Suzanne Ullman. Constraints about depictions of violence where given, but not as a general ban, rather in dialogue about being age appropriate for the target audience (as identified by Gathering the Voices). Suzanne is a platform game, which allows players to control Suzanne’s movements through spaces in Budapest, whilst looking for items that extend the testimony snippets available to them.

Screenshot from Suzanne, with permission from Gathering the Voices.

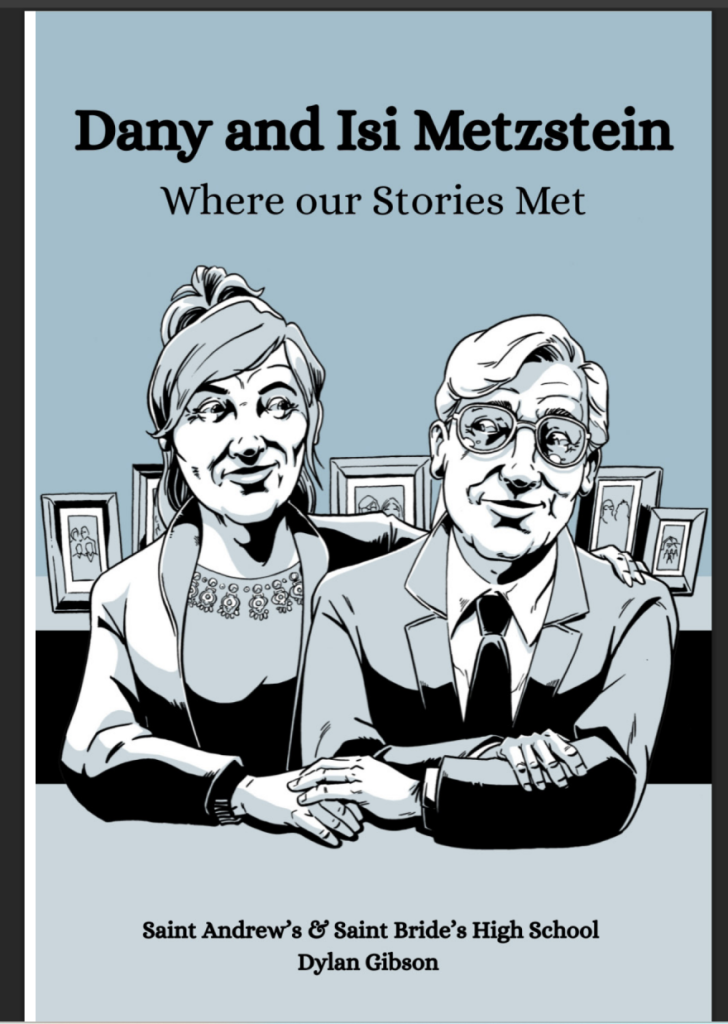

Unlike Marion, when Dany Metzstein discovered school pupils were proposing to create a digital comic book about her life and that of her husband Isi Metzstein, she was more dubious. However, she was persuaded by her own children that comic books can tackle serious topics too. Dany and Isi Metzstein: Where Our Stories Met was published in June this year (2025) and like the games, is freely available on the Gathering the Voices website. The comic book was created through a 4-month co-creation process led by Magic Torch Comics. To begin, they taught pupils about comic genres, and visual storytelling in this format, including a range of examples including Maus. Then trustees from Gathering the Voices offered a contextual background to the Holocaust, their collection, and the Metzsteins. Pupils then diligently explored the testimonies, highlighting sections to keep for the comic, and scoring through those that had to be cut. Like the game developers for Suzanne, they carried out research about the time and places featured in the testimony and evidenced a strong sense of responsibility to this past, and to the particular survivors related to their project. In both cases, Holocaust education emerged through the creativity process. But it was student-led and experiential.

As Paul Bristow said in interview, it really was a matter of process over output. It didn’t matter if the comic was ever published (and ditto for the game), but the process of developing it built several transferrable skills for the students whilst deeply immersing them in learning about the Holocaust. For the games projects, these were students who were less likely to encounter ‘the Holocaust’ as a topic in their university studies and had little previous knowledge in most cases, thus this was Holocaust education breaking ground into creative and technical sciences.

Cover image ‘Dany and Isi Metzstein: Where Our Stories Met’, with Permission from Gathering the Voices

Gathering the Voices is an example of the importance of contextualising the Holocaust within local history, and of using digital media not simply to disseminate information about this past but as powerful learning tools. Angela Shapiro of Gathering the Voices stated that unlike many Holocaust organisations, they’ve never been hesitant about ‘games’ because they do not treat games as simply entertainment spaces for Holocaust-related content, but as processes that enhance students’ technical, creative and employability skills, and confidence, give them responsibility for their own learning, whilst trusting them to apply these skills to developing a respectful depiction of survivor testimony.

Yet, it is also exemplary of the risk to Holocaust memory. The entire Association relies on the dedication of 6 individuals. What happens when they are no longer willing or able to manage it? Planning for technical sustainability is one thing, but behind interfaces and technical solutions is an astonishing amount of human labour, which like the testimonies in the collection will one day need to be passed onto the next generation. Who will take responsibility for these interviews then? How do we ensure all this tireless commitment and free labour is not for nothing.

The Landecker Digital Memory Lab is currently carrying out the largest survey of global digital Holocaust memory practice. Do you work at a Holocaust-related organisation? Whether you have minimum or substantial digital engagement, are a tiny or very large organisation, we want to hear about your digital strategies, projects and procedures. Find out more about the survey here.

Want to know more?

Our previous Spotlight blogs include reviews of digital projects at:

Falstad Centre (Norway)

Dachau Memorial (Germany)

Auschwitz Jewish Centre (Poland)

Zanis Lipke Memorial (Latvia)

Melbourne Holocaust Museum (Australia)