Digital data spaces: the future of European Holocaust data?

What is a data space and what are the preconceptions around them? Our Lab Director interviews Pavel Kats, Coordinator of the European Memory Data Space Blueprint project and discovers why the data space movement is at a critical point and crucially, why Europe needs a data ecosystem dedicated to Holocaust memory.

Victoria Grace Richardson-Walden: What is a ‘European Data Space’?

Pavel Kats: Common European Data Spaces (https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/data-spaces) are a bold innovation attempt by the European Commission to fundamentally rethink how we share and use data. They’re being funded and launched in many fields, from business sectors like industry and transport to societal domains like cultural heritage, to help individuals, businesses and institutions address the main digital challenge of our times: the growth of data and our inability to efficiently put it to use.

For data to bring value, it must be used: in different ways and by different tools; across borders, stacks and institutions; and by different audiences. Yet, traditional data architectures are not built for that. In cultural heritage, we see it better than anywhere else. Every aggregation platform, whether national, European or thematic, at the same time exposes, suffers from and often exacerbates the same set of problems: chronic institutional vendor lock-in, poor support for multidirectional data exchange, extreme fragility of data interfaces, which break links and identifiers every few years.

All these turn the vision of interconnected data ecosystems into a pipe dream – and a nightmare for those who build them. Data projects and infrastructures come and go, each creating another silo instead of solving the root cause. Worse, they add to the problem by creating the sustainability dilemma: either maintain new components, adding to the cost of the project, or get rid of them losing value, investment and reputation.

We are trapped in the vicious cycle of launching overlapping, poorly compatible data platforms and infrastructures with short lifespans, instead of stopping to rethink how data sharing should really work.

European Data Spaces is an attempt to do exactly that. Their core features are data sovereignty and moving towards decentralization: a recognition that data should be managed and governed by its owners or guardians, as with museums and archives, close to its original source. Decentralized data ecosystems, based on shared standards and governance would offer an alternative to centralized platforms. Data holders retain long-term sovereignty over their data, deciding how it is accessed, used, enhanced and, when relevant, monetized.

In line with prof. Pierre Luigi Sacco’s Culture 3.0 vision, institutions, communities, but also individuals and even algorithms, become active participants, empowered to be at once providers, consumers and value creators. By abandoning the tired provider-consumer dichotomy, we have a chance to venture into new levels of creativity and collaboration across society and give substance to Europe’s claims of digital sovereignty.

It’s an ambitious vision, but as often in Europe, innovation drowns in bureaucracy and overengineering. Many data space projects speak in high-level abstractions or avoid the hard work of practical broad-scale innovation. Data architectures, such as the Simpl project, are overly complex. Three years after launch, the data space movement is at a critical point: it is expedient that real data spaces emerge in a year or two to keep the momentum going.

What will it do, and what will it not do?

The best way to start the answer is to do a thought experiment. Imagine asking someone a couple of years before the Web entered our lives what it would do. Quite possibly, we are now just a couple of years before a future in which we have a totally new way of handling data. Think about a world in which data firmly belongs to where it originates – a person, organisation, device, object – without mediation of any specific app or platform.

You would not think of accessing an archival collection via their online collections, or an app, or an aggregator, or just anything else. It’s just there and you can access it – via all those and just anything else that anybody can develop – subject to the archive’s concerns and on their terms. You can also change it – also on their terms.

It’s like the shift between sending around multiple versions of a Word document and managing the changes and sharing one version of a shared document and assigning different roles to recipients. Now think about such kind of reality but for any kind of data, and not mediated by one infrastructure company like Google, but by a European, or universal, open standard.

The breadth and impact of applications is mindblowing. Any app or platform can access and display any data item or collection in the data space. You can work with the same data from any platform and there is no need to synchronize updates because it is done by the data space for you. Platforms become the lenses through which you look at the data, not the data itself. It’s like browsers and web pages – you can access the same page from multiple browsers – but with data.

Back from the thought experiment to reality, there is currently no one single understanding in Europe of what a “data space” actually is. Many still consider it as a new label for traditional data aggregators, for example, when you hear someone speaking about “adding another collection or dataset” to the data space. This thinking misses the fundamental point: if you still need to make a special effort to contribute data to the data space, then nothing has really changed.

Another misconception, in my view, is reducing the data space to a shared catalogue of datasets or term vocabularies. This might be a “dataset space” at best, but it would not solve the challenges of data exchange in scale if reusing data would require renegotiation of terms and building technology each time anew.

Dutch Digital Heritage Network (https://netwerkdigitaalerfgoed.nl/) publishes every night the updated catalogue of thousands of datasets from hundreds of heritage institutions across the country. This is probably one of the most advanced national data space projects across Europe. Yet, data spaces should go much further.

Data spaces are an opportunity to fundamentally redesign the way we are managing and using data. Check the projects like Solid Project or Post-Platforms, in which Jewish Heritage Network – of which I am Co-Founder – is a partner. These projects implement sovereign data by design by storing it on pods or personal online data stores. These projects can vary in the degree they are ready to challenge the status quo, but they share one fundamental feature: separation between the data and the platform and sovereign management of the data independently from its use. This would make the dream of the new web of data that we started with possible.

Where does the premise of a ‘data space’ come from, and how are you hoping to connect with existing data space strategies?

The premise of a “data space” is a simple realisation: our current ways of sharing data don’t scale. Across Europe, you can see different strategies for building data spaces. Some see them as large but still closed environments, often with proprietary trust frameworks and standards. Others aim for more open and democratic ecosystems.

For societal domains like cultural heritage and memory, closed models are not an option. These sectors hold massive and diverse collections across thousands of institutions and communities. These collections can only shine in open ecosystems where all the stakeholders are active participants. In Holocaust memory, for example, personal archives and family stories should belong to the data space alongside institutional collections.

What’s interesting, and often missed by the more “industrial” data spaces, is that societal domains present difficult challenges and unexpected requirements in terms of inclusivity, ethics, data diversity and longevity.

“When the European Commission speaks about ‘devising new ways of remembrance’ in the age after the last survivor, is it a slogan, or a call for real responsibility to ensure that materials remain accessible and usable?”

What other data spaces exist or are in the works, and what lessons have been learnt?

The European Commission currently supports Common European Data Spaces in 14 different domains (https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/data-spaces), covering areas such as cultural heritage, tourism, media, skills, health, and more.

But the term has become fashionable, and many existing data-sharing initiatives are now rebranding themselves as data spaces. The problem is that relabelling alone doesn’t change anything. Without infusing it with new thinking, a “data space” is just a traditional data aggregator, or a data ecosystem without enough glue to hold it together after the funding period.

The main lesson from other initiatives, especially those not funded by Europe, is that data spaces must show real value in data sharing, which has nothing to do with European funding cycles. Public money can launch innovation, but if a data space can’t sustain itself, at least partially, through the investment and commitment of its members, then it’s not worth starting

Our project’s own bold assumption, with one year to prove, is that Holocaust memory can be that kind of domain. If we succeed, our emphatic plea to the European Commission will be simple: Europe needs one more data space, dedicated to Holocaust memory.

Why do we need one specifically dedicated to Holocaust memory, and who is it for?

This question, indeed, comes up often. People wonder why we need a data space dedicated to Holocaust memory, different from the one for general cultural heritage. It is because Holocaust memory has several unique characteristics that set it apart. Holocaust memory actors are not only museums and cultural institutions.

The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) has come with a very clear definition and a set of guidelines about what we should include under the category of Holocaust-related materials. It is clear that many types of materials would be found in public administration archives, judicial sources, personal archives, and global repositories with a unique mandate, such as the Arolsen Archives.

But it is really not only about the sources, as Holocaust memory is a domain with unique historical and societal relevance and educational mandate. Dealing with Holocaust-related materials requires specific sensitivities in order to respect the dignity of victims. The rate of denial and distortion is growing, which makes it necessary to invest in increasing digital and media literacy of those using these materials.

Finally, Holocaust memory is characterised by the unique international legal and institutional framework built over years to keep it alive — shaped by IHRA, UNESCO, the EU, the Council of Europe, the UN, and leading institutions like Yad Vashem, the USHMM, and the Arolsen Archives.

All this makes the case for a dedicated data space for Holocaust memory, one built not just for efficiency, but for responsibility, truth and the singular societal mission.

Why should we care about a data space for Holocaust memory?

The Holocaust should be remembered as the foundational legacy of the European Union, a defining event that continues shaping our understanding of human rights, freedoms, and respect for diversity.

When the European Commission speaks about “devising new ways of remembrance” in the age after the last survivor, is it only a slogan, or a call for real responsibility today to ensure that materials remain accessible and usable? We are accustomed to using strong words when working in Holocaust-related projects, but we should really stop and ask ourselves what they truly mean to us today.

For me, they mean that everyone working in the field – researchers, project managers, software developers – should see as their priority to make Holocaust-related materials accessible and resonant for future generations.

The Holocaust happened some 80 years ago. Can we be certain that the materials we digitise today will remain accessible to guide teaching and learning about the Holocaust 80 years from now? This requires a shift: from the short-termism of today’s projects to long-term thinking on sustainable infrastructures and ecosystems.

Data spaces offering such a vision, albeit not without problems, are Europe’s best chance to gain digital sovereignty. And if there is one domain, where Europe has a clear historical mandate to do so, it is in Holocaust memory.

Who is leading this initiative?

The initiative is led by Jewish Heritage Network, a Dutch non-profit dedicated to using innovation to preserve and promote Jewish heritage and culture. Envisioned as a true grassroots collaboration, the first phase, dedicated to designing the conceptual blueprint for the data space —the EMDS – Blueprint project — is funded by the European Commission’s Citizens, Equality, Rights and Value program.

It consists of a series of co-creation encounters with professionals working in Holocaust memory: archivists, educators, city leaders, and heritage organizations.

We’re lucky to have an exceptional consortium of partners, each acting as a conduit to their own communities. Terraforming and Centropa connect us with educators and “gatekeepers” such as archivists and librarians. Post Bellum works with the Stolpersteine network in Czechia, one of the key beneficiaries of the future data space.

The European Association for the Preservation and Promotion of Jewish Culture and Heritage (AEPJ), brings in European small and medium organizations devoted to preserving and sharing Jewish heritage. The Combatting Antisemitism Movement (CAM) connects us to cities through their signature events for European mayors. Through our partnership with the Post-Platforms initiative, we’re also engaging directly with the wider community of data space projects and specialists.

“Everyone working in the field – researchers, project managers, software developers – should see as their priority to make Holocaust-related materials resonant for future generations.”

Can you talk through the process of the project?

Glad you asked. The three years of data space development by Europe have made it very clear that we need a fundamentally new way to explain and communicate what data spaces actually are. The simple truth is that despite major investments – dozens of projects and hundreds of events – most heritage and memory practitioners still see data spaces as a new label for familiar concepts.

The EMDS project makes visual communication its priority – as the medium that can effectively convey what data spaces can be and why they matter. As ecosystems connecting thousands of users and billions of data items, and enabling entirely new applications, data spaces should be truly fascinating and groundbreaking!

But since data spaces started a few years ago, we have lost somewhere the initial excitement about this strategic innovation. To revive it, people need to see the potential with their own eyes; how data spaces can connect their data and their work to a bigger whole, to peers across the globe, and power previously unthinkable educational and storytelling experiences. The project has already started developing Visual Blueprint as its central communication resource.

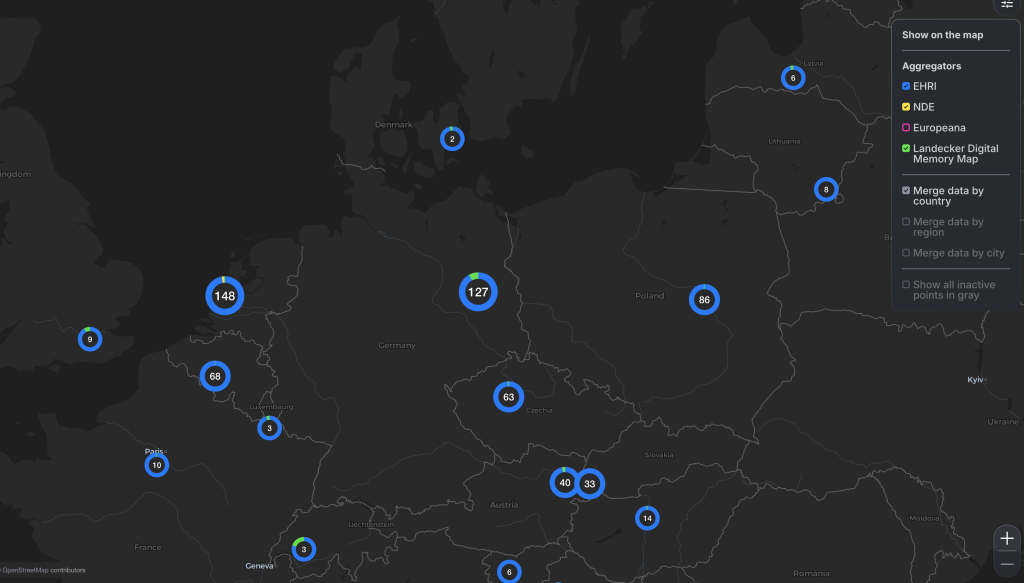

The first step in designing the new ecosystem is understanding the data itself: what data are we talking about? Where is it? What is the digitisation status and rate? We are fortunate to have the aforementioned IHRA’s working definition of Holocaust-related materials and accompanying guidelines, but we also need visual means to communicate the diversity and scale of these materials, in Europe and beyond. This is our first step, and some work has already begun, relying on the unique dataset about Holocaust-related collections, compiled over years by the EHRI project.

Much of this data cannot be shared for a variety of reasons – from complex legal and regulation considerations and clashes between them (as in the case of online publishing of records from CABR – Central Archive for Special Jurisdiction in the Netherlands) to copyright restrictions and ethical concerns about sensitive or graphic content.

Even when no explicit legal obstacles exist, often institutions do not publish materials because of organisational inertia, lack of skills, or restrictions of technical stacks which stand in the way. Sometimes, institutions do not have the leverage against software vendors managing the archive, who would charge additional costs for the publication. As data space designers, we need to thoroughly understand the landscape of these constraints, how they interact, and their overall impact. Only then can we design a data space capable of addressing them in the long term. We need the help of the community in inventorizing these constraints.

Before we move on to devising the new data-sharing architecture for EMDS, we also need to study existing initiatives – such as Europeana (now evolving into a data space), EHRI, and national initiatives, such as NDE in the Netherlands. Their lessons are essential.

Finally, we must focus on the purpose: how Holocaust-related data is – and can be – used in teaching and learning about the Holocaust. What digitally-powered experiences already exist, and which ones need to be created? What requirements do memory professionals – researchers, educators, activists – have for different tools and technologies? Here we hope to collaborate closely with the Digital Memory Database by Landecker Digital Memory Lab, that can provide invaluable insights into the challenges and opportunities for today’s digital memory projects, and into the experiences of those building them.

This is the core plan. Crucial to it are the ongoing meetings with different communities of memory professionals, each one helping us refine specific use cases of the future data space based concrete examples from their practice. Without clear and specific use cases for the data space, it will be difficult to advocate for its importance. More importantly, it will be difficult to specify the technical and non-technical requirements for the future ecosystem. That’s why we are inviting research groups and communities to work with us in articulating these use cases together.

“What digitally-powered experiences already exist, and which ones need to be created? What requirements do memory professionals have? Here we hope to collaborate closely with the Landecker Digital Memory Lab.”

What work has been done so far and what have you learned?

We held our kick-off series of events in June in Amsterdam and a fourth event, From Data to Blueprint, in October in the Hague.

At both events, we were proud to host leading figures from the European memory community. The main takeaway so far is clear: we need to articulate, with precision, why a dedicated data space for Holocaust memory is necessary — and what concrete use cases it will make possible.

At your meeting in Amsterdam, the shift from portals to data spaces and ‘data space fatigue’ were discussed. Could you explain what these are?

Anyone who’s worked in the heritage field for a few years has seen the endless churn of data portals come and go. It’s clear that we need new solutions for managing and sharing data. Data spaces could be that way forward. The fatigue isn’t just with data spaces; it’s with public innovation more broadly.

There’s a growing gap between the breathtaking progress of information technologies, especially AI, unfolding in front of our eyes, and the stagnant reality inside many memory institutions. Many rely on legacy systems from two decades ago, locked into vendors and cut off from the real value that public innovation could bring. The potential for change is enormous. The question is whether Europe will seize this opportunity.

What are the biggest challenges in both creating the blueprint and implementing it?

The biggest challenge is collaboration. We are not short of amazing technologies that can turn a digitized collection into a richly annotated, multilingual, contextually linked information resource. Funding isn’t the biggest problem either.

The real challenge is reaching a critical mass of institutions and major initiatives that can recognize that we can’t keep operating in siloed platforms if we want real impact – in heritage, in memory, in cultural tourism. We need to invest in collaborative ecosystems that can find the right balance between centralisations and decentralisation — so that what we build today will serve our children many years from now.

How can we support professionals working in Holocaust museums, memorial sites, archives and libraries, and broader heritage and education to engage in conceptualising the materials they work with as ‘data’ to ensure their long-term maintenance and security?

This question goes beyond the scope of our specific project, but it touches on something fundamental. As a field, we still lack the capacity to truly understand the digital. And I do not mean the usual complaints about ‘lack of digital skills’ – these are quite often misplaced.

We are missing the ability to grasp how digital is transforming the very foundations of our work. Digital is still treated too often as a department – sometimes even a sort of marketing – or just an innovation playground, detached far from the core stack. It is incredible how short-term our digital thinking still is.

The longest sustainability horizon we can imagine is a few years, including 2-3 years of formal “post-project” sustainability commitment. What if we required every project to ensure its outcomes remain available for 20 or 50 years?

How would this change our approach to persistent identifiers, vendor selection, data architecture, repository replication, or change management? We need training curricula for heritage professionals that are not afraid to address these existential questions. Only then will we start seeing everything as data – possibly, not digitized yet – and if we want our digital artefacts to live long, we need to think, plan and train ourselves differently.

How can people get involved in your project, and who would you like to see at your events?

If you’ve made it to the end of this interview, you’re probably interested, so thank you. The best way to start is by following our LinkedIn project page, where we regularly post updates, reflections, and invitations to upcoming events.

In the coming months, we’ll host a series of events across Europe, and everyone is welcome to join and contribute.

We especially want to meet people who care about the long-term sustainability of Holocaust-related data and who reflect on the potential of broad access to data for transformative teaching and learning. This field is of singular importance for Europe, and we’re at a unique moment of opportunity for innovation. Join us.

-

- You can view the videos from the visionary speakers who contributed to the kick-off event, including the Director of the Landecker Digital Memory Lab, Prof. Victoria Grace Richardson-Walden here: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/kicking-off-emds-vision-interconnected-ecosystem-p22we/?trackingId=1h2Nd0fPsGxfI%2B8dxRFo7Q%3D%3D